Things were rocky for Cavanaugh from the start. "I'd been commissioned out

of UCLA in artillery. All my contemporaries got orders to active duty

while I stood around for a month and got assigned to the Ordinance

Department. They basically handle ammunition and supplies, which felt like

a real downgrade."

Not a man to nurse his regrets, Cavanaugh immediately applied for

the best

bet to get him out of ordinance work - parachute training. "Parachute

training is the kind of thing that the dumb guys at army orientation

volunteer for," he admits. He finished jump school in October of 1942 and

was assigned to the 505 pending activation of the 511th Parachute Infantry

Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Orin Haugen.

"The first time I met Col. Haugen was not a pleasant

experience," Cavanaugh admits. "We assembled at the 'frying pan' area of

Fort Benning, where the regiment's cadre of staff and commanders were

first gathered together. I think I was only the 5th officer in the

regiment. I reported in and Haugen snarled, 'What the hell are you doing

here? You're an ordinance officer!'

"He wanted nothing to do with Ordinance, but neither did I! So he

had to

tolerate me." Haugen's tolerance consisted of giving Cavanaugh the worst

duty available, police and prison officer. "I spent that month in the

'frying pan' going down to the prison to pick up prisoners and bringing

them back to clean up the area."

Once the officers were assembled, the regiment moved to Camp

Toccoa,

Georgia to receive its first enlisted troops. "It was raining and sleeting

outside and we didn't have anywhere to stay, so they put us in a school

auditorium on cots," Cavanaugh remembers. "We wore our 'pinks and greens,'

dress blouses with gray trousers and shiny jump boots. Our first day

there, ol' Haugen took us up Mount Curahee, two miles up a muddy,

serpentine road. 'You guys are gonna run that every day,' he told

us."

Cavanaugh finally managed to break the ice with his new commanding

officer

a month later, when all the officers ran up the mountain in a timed

race. "I came in 3rd out of 30 or 40 officers. He didn't say anything, he

was never one to tell you you'd done a good job, but he noticed. He was a

great runner, he loved to run. One of my first impressions of the colonel

was him soaking his feet in a pan of alum solution to toughen

them."

Running was the regiment's trademark activity. "We were

pretty

cocky," Cavanaugh admits. "Parachute troops always are. General Swing, the

division commander, felt he should do something to take the wind out of

the regiment's sails." First the general tried to make the 511th wear

leggins, the tall boots other soldiers wore, instead of their jump

boots. "Our guys cut them off and that drove Swing wild," Cavanaugh

chuckles. So the general started the 'Swing runs,' assembling hundreds of

division officers two or three times a week for a work-out. "He always put

the 511th officers at the end, because that's the toughest place to

run," Cavanaugh remembers. "When it was over and the rest of the officers

were huffing and puffing, we'd take off and sprint back to our regimental

area, Col. Haugen leading the way."

Besides running, Haugen loved horse-back riding and polo. His wife

Marion's horse, Whiskey, has a prominent burial site at Fort Snelling. But

Marion never followed her husband to his duty sites. "He was determined to

have the best regiment in the army," Cavanaugh explains. "No dereliction

of duty, no fooling around. Very few men brought their wives with

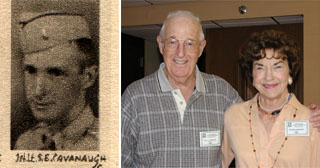

them." When the regiment moved to Camp Machall (or Mackall) to begin

intensive training, Cavanaugh brought his bride, Blanche, stashing her in

the nearby town of Aberdeen. "We had to be at camp at four in the morning

and weren't supposed to go home at night except on weekends. We worked

until dark or even all night, but whenever possible, some of us would duck

out." But Blanche remembers a gracious side to her husband's

commander. "I've been kissed by him," she smiles. "He kissed every bride,

and he presented me with a platter with the 511th insignia on it, which

I've kept to this day."

"He didn't socialize much," Cavanaugh says when asked if

the

colonel had friends. "He selected some old timers he was familiar with to

be company commanders, people he respected. He may have had close friends

but I never knew of any."

Haugen's nickname, 'Hard Rock Haugen' ("Not to his

face," Cavanaugh admits), stemmed from his reputation as a tough

taskmaster. "He set high standards," Cavanaugh says. "At the end of each

phase of training, he'd get up on a podium and give his famous cross-roads

speech. 'You men are at a cross-roads,' he would say. He was always

setting the example and insisting that we had to do better."

At Camp Machall, Haugen gave Cavanaugh leadership of a

platoon in

A company, which thrilled the young officer. But those high standards were

always a concern. "He told junior officers, 'When you leaders fail to

accomplish your mission, you are responsible for all the men you lose.'

That scared the platoon leaders to death. If a man failed to jump, it was

our fault, and some platoon leaders were relieved [fired] after their men

froze in the door of the plane."

Basically, Cavanaugh insists, Haugen didn't want his men

killed. "He wanted us to take care of ourselves." Once, after Cavanaugh

became a liaison officer between Haugen and the regiment's division, he

participated in a night jump in the rain. "As liaison, I had to hunt down

the division personnel, get a message, and bring it back to Col. Haugen's

tent. I came back soaked to the skin, feeling like the heroic character in

Message to Garcia, and all Haugen said was, 'Dammit, didn't you have a

raincoat?'"

Toughness and standards paid off when the regiment was

deployed

overseas to fight the Japanese in the Philippines. "We were given a

mission to launch an operation to cross a mountain in unmapped, uncharted

territory," Cavanaugh recounts. "It started out as a reconnaissance

mission; we were trying to link up with the 7th Division on the other

side." The Americans had hired some Filipinos who were familiar with the

area to lead them and they led the troops into an ambush.

"The Colonel was with C Company, the lead company. We

didn't

proceed in a big column or anything; we were progressing in a series of

leap-frog movements. On the second or third day, C Company was ambushed

and Colonel Haugen and his staff were isolated and cut off." To the

regiment's amazement, Colonel Haugen eventually fought his way through the

mountainous jungle terrain to rejoin his regiment. One soldier wrote of

the incident, "Only a man with Haugen's instincts and resources could have

accomplished that feat. His superior training and physical conditioning

unquestionably saved their lives."

For his men, the toughest thing about Orin Haugen may have

been

his death. On February 11, 1945, he was hit by a fragment from a 20mm

anti-aircraft shell that the Japanese were firing at troops. "It caused a

sucking wound in his chest," Cavanaugh explains. While accounts of the

specific cause of death vary, Cavanaugh

supports the theory that Haugen died when his wound exploded from a change

in cabin pressure as he was being flown to a hospital. "He bled to death,

but it shouldn't have been a fatal wound."

According to William Haugen Light, Orin's son, "My dad died of his wounds

on February 22, 1945." He'd been taken to "the historic church in

Parañaque with the bamboo organ where he was initially operated on

by the regimental dentist." The surgeons were reportedly busy with other

patients.

Col. Haugen was then evacuated to Mindoro Island, Light

reports, where he was visited by his old friend, Colonel George Jones,

later a brigadier general, then CO of the 503rd Parachute Regimental

Combat Team "just before the 503rd was to jump onto Corregidor Island to

wrest it from the Japanese." As he was being flown from Mindoro to New

Guineas for additional surgery, "He had asked a nurse aboard the plane

for, and been given, a cigarette. When she returned to his litter he had

hemorrhaged and bled to death."

The loss was devastating for his men. "I learned so much

from

him," Cavanaugh insists, to which Blanche adds, "His men respected him so

much." "It can't be," wrote one of them upon hearing of Haugen's

death. "Not our Rock."

|